RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS: CANADA’S SHAME. TRUTH & RECONCILIATION

|

TRUTH & RECONCILIATION WHAT DOES IT MEAN? AND RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL: CANADA’S SHAME “How smooth must be the language of the whites, when they can make right look like wrong, and wrong look like right.” (Black Hawk, Sauk) “Truth and Reconciliation Commission commenced 2008 and closed December 15, 2015. It was an exhaustive process culminating in 94 calls to action to redress the horrific legacy of residential school. It was all there in the report, yet it took the finding of the bones of 215 Indigenous children on the grounds of a former residential school in Kamloops, B.C. six years later for it to finally sink into the hearts and minds of Canadians and wake up indifferent politicians.” (Shannon Thunderbird, Tsm’syen Elder) “Today, if you haven’t yet begun to educate yourself as to what is meant by Truth and Reconciliation as it pertains to First Nations, Metis, and Inuit, when you have done so, you will understand what is needed for Reconciliation. Never let Truth and Reconciliation become a cliche for government passive inaction. Stand up for what is right!” (Kate Dickson, Tsm’syen Elder, September 30, 2021) |

|

JOHN TRUDELL “Too many people (Excerpt from his poem, Crazy Horse)_____________________________________ “When we arrive on earth, we have already entered the reality of the already dead, spending lives waiting to die. The reality is one of the spiritually disconnected…Leadership, institutions and other things held up to esteem, yet none of them have any spiritual relationship to life…no spiritual recognition. In the technological world, we no longer remember the original dream, ancestors, teachings or the knowledge…it is almost like they are spiritually disconnected from the past. The conditions we live in now, with the way that the cancers of greed, and war have spread, and no one has taken responsibility to effectively deal with these things. We have emotional outbursts, but there is no practical answers to deal with it….There is no spiritual relationship to their descendents…in the shape of the future. This disease is eating up the spirit and they don’t know it is happening. They only react as humans, but have no relationship to ‘being’. Protect your spirit because you are in the place where spirits get eaten.” (Excerpts from a 2003 YouTube Video). |

|

TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was launched in 2008 and closed December 16, 2015. The final report included 94 calls to action to redress the legacy of residential schools. The Commission’s task was to reveal past government wrongdoing in the hope of resolving deep conflicts. It is important to note that systemic racism that found its genesis in colonialism is embedded in Canada’s legal, political and economic contexts. This is despite government so-called commitments to strive for reconciliation. The term ‘Reconciliation’ includes honoring and acknowledging our treaties. Canadians need to be educated about them; unfortunately they are not included in any educational system. Reconciliation also means two disparate groups becoming ‘friendly’ again and agree to cooperate in good, supportive ways. This includes total accountability for past deeds. What has happened since the final report was released.

Both racial bias and systemic racism, that have been so engrained in people for hundreds of years is extraordinarily difficult to change. Yet it must be done; it must be a dedicated national movement with people of good like minds leading the way. We are the ORIGINAL PEOPLE. On Tuesday [June 2, 2015], Canada received the findings and calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Sobering? Provocative? Challenging? Ambitious? I hope so. “For the past six years, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission travelled the country gathering statements and documents from survivors, inter-generational survivors, government and church archives. I was one of those people out there in the field with the Commission. As the director of statement-gathering, I heard the pain of survivors. I saw the elders cry. What we heard was shocking. Going in, we all understood that this work was going to be tough. But I don’t know if I truly understood just how far-reaching the effects of the schools were, how deep the scars run from this misguided approach to education. From coast to coast to coast, and everywhere in between, we saw tears, we heard pain and we saw men and women somehow summon the courage to get up, sometimes in rooms full of complete strangers, and reveal some of the most difficult moments in their lives. All in the name of truth, and with the hope that somehow, somewhere, people would listen. Now, these statements, documents and other materials collected by the TRC will make their way to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. This transfer realizes a vision the drafters of the settlement agreement had – that at the end of the Commission’s mandate, a permanent body would be established to ensure these memories are never forgotten, that they cannot be forgotten.” |

| Fort Fraser BC., the Lejac Residential School. Allen Willie (age 8), Andrew Paul (age 9), Maurice Justin (age 8), and Johnny Michael (age 9) fled the school New Year’s Day,1937, “without caps and lightly clad” and made it six of seven miles to their destination but froze to death on the ice just a kilometer from their reserve.

“Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is overseeing something called the Missing Children Project–a bold attempt to track and record the fate of every indigenous child who passed through the notorious residential school system. It’s a kind of census of calamity….But the TRC’s most challenging task may involve not the living, but rather the dead. Its Missing Children Project, headed by Ontario historian John Milloy, is seeking to create a comprehensive record of every child who never returned home. What are the numbers, 5000? Or, as some suggest, as many as 50,000? Did they die from TB or malnutrition? Where are the medical records? Did they die while fleeing abuse at the hands of their teachers? Where are they buried? Or if they survived, did they return to their homes, or were they passed on to foster parents? Was this genocide, as some suggest, or a monumental act of carelessness, as Milloy characterizes.” Why should we concern ourselves with things that happened 70 or 80 years ago? What relevance do events like the Lejac incident have today? Milloy sees his project as a fundamental historical settling-of-accounts. For Canada’s Aboriginal peoples, though, it’s much more than statistics. Says native activist Maggie Hodgson: “It is so important to know how we came to this place of collective grief. If we have these figures, then our people can begin to talk about their own holocaust.” (http://claudeadams.blogspot.ca/2011/07/what-happened-to-children-collaborative.html) |

| THUNDERBIRD’S RESPONSE

Definition of Genocide – From the Greek, genos, meaning race, kind + -cide that first applied to the extermination of the Jews by Nazi Germany. The systematic killing of, or a program of action intended to destroy a whole national or ethnic group.” Webster’s New World Dictionary, 3rd edition, 1994. Definition of Assimilation – “Cultural absorption of a minority group into the main cultural body.” (Ibid). Genocide has since become ‘assimilated’ into the cultural lexicon of modern times and the word now applies to any attempt to destroy another culture. Perhaps, in the case of First Nations, we should have our own word. I propose, ‘Genoassimilationism’. Definition: The absorption of Canada’s First Nations into the dominant Canadian social and economic body politic through the systematic destruction of Indigenous culture. In other words, what happened to First Nations people was not a “monumental act of carelessness”, as Milloy suggests, but a deliberate, systematic goal of Indigenous absorption into the dominant culture through heinous means, that included the horror of residential schools in which the clergy engaged in rape, murder, starvation, and physical and emotional beatings. Whereas ‘carelessness’ has an aura of carefree untroubled behaviour; not thinking before one acts, for example, Genoassimilationism lays the blame exactly where it should be, at the doors of the churches and the federal government. |

| TORONTO STAR – SATURDAY, JUNE 9, 2011

“There’s no exact tally, but hundreds of First Nations children disappeared after being taken from their homes to attend residential schools from 1870 to the mid-1900s. That’s the most startling discovery for Murray Sinclair, the Manitoba judge who is chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, examining the effects of residential schools on First Nations Communities. “Missing children – that is the big surprise for me,” Sinclair said in an interview during a Toronto visit this week. “That such large numbers of children died at the schools. That the information of their deaths was not communicated back to their families.” Thunderbird’s Comment: Manitoba has a very large population of Indigenous people; isn’t it odd that Manitoba’s first Aboriginal judge, appointed to Manitoba’s Court of Queen’s Bench in January 2001, would have no idea of the death toll, and didn’t or couldn’t make the leap to a correlation between violent, hate-based crimes on such a huge scale and death. For thirty years, Judge Sinclair’s main legal interests were civil, criminal and Indigenous law! The Star article goes on to say that the number of deaths are in the hundreds, when, the estimates have also been estimated at between 35%-60% of the approximately 150,000 children who were kidnapped and savaged. 1909, Dr. Peter Bryce, general medical superintendent for Indian Affairs reported to the Ministry that between 1894-1908 the mortality rate in western Canadian residential schools was between 35%-60%. The statistic became public in 1922 (more about this below), That is between 52,500 – 90,000 children unaccounted for! Do we all really naively believe they died of natural causes? Mass graves have already been discovered. It is our holocaust. The good judge had a breakfast meeting with power brokers from universities, the media, business and banking at the National Club; “He said it’s important for the story of the schools to spread from our educational system to the corridors of corporate power.” Does he think we haven’t tried and tried? Who really wants to hear that our country and churches, bastions of supposed trust and reliability, are responsible for so many innocent deaths. Perhaps what might have been more compelling was to have some residential school survivors tell their story of humiliation, physical trauma and starvation over eggs benedict at the National Club; however, it probably would have required a set of squirm-proof chairs. |

|

CANADIAN GOVERNMENT FINALLY APOLOGIZES June 11, 2008, 1.00 p.m., Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper stood up in the House of Commons and offered a full apology on behalf of all Canadians to those Indigenous people who were part of over one hundred years of residential school atrocities. It was a landmark day in the history of Canada, for this was the first time a sitting Prime Minister apologized to the First Citizens of this country.

“Mr. Speaker, before I begin officially, let me just take a moment to acknowledge the role of certain colleagues here in the House of Commons in today’s events. Although the responsibility for the apology is ultimately mine alone, there are several of my colleagues who do deserve the credit. First of all, for their hard work and professionalism, I want to thank both the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and his predecessor, now the Minister of Industry. Both of these gentlemen have been strong and passionate advocates not just of today’s action, but also of the historic Indian residential schools settlement that our government has signed. Second, I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge my former colleague from Cariboo—Chilcotin, Philip Mayfield, who for a very long time was a determined voice in our caucus for meaningful action on this sad episode of our history. Last, but certainly not least, I do want to thank my colleague, the leader of the New Democratic Party. For the past year and a half, he has spoken to me with regularity and great conviction on the need for this apology. His advice, given across party lines and in confidence, has been persuasive and has been greatly appreciated. I stand before you today to offer an apology to former students of Indian residential schools. The treatment of children in these schools is a sad chapter in our history. For more than a century, Indian Residential Schools separated over 150,000 Aboriginal children from their families and communities. In the 1870’s, the federal government, partly in order to meet its obligation to educate Aboriginal children, began to play a role in the development and administration of these schools. Two primary objectives of the Residential Schools system were to remove and isolate children from the influence of their homes, families, traditions and cultures, and to assimilate them into the dominant culture. These objectives were based on the assumption Aboriginal cultures and spiritual beliefs were inferior and unequal. Indeed, some sought, as it was infamously said, “to kill the Indian in the child”. Today, we recognize that this policy of assimilation was wrong, has caused great harm, and has no place in our country. One hundred and thirty-two federally-supported schools were located in every province and territory, except Newfoundland, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. Most schools were operated as “joint ventures” with Anglican, Catholic, Presbyterian or United Churches. The Government of Canada built an educational system in which very young children were often forcibly removed from their homes, often taken far from their communities. Many were inadequately fed, clothed and housed. All were deprived of the care and nurturing of their parents, grandparents and communities. First Nations, Inuit and Métis languages and cultural practices were prohibited in these schools. Tragically, some of these children died while attending residential schools and others never returned home. The government now recognizes that the consequences of the Indian Residential Schools policy were profoundly negative and that this policy has had a lasting and damaging impact on Aboriginal culture, heritage and language. While some former students have spoken positively about their experiences at residential schools, these stories are far overshadowed by tragic accounts of the emotional, physical and sexual abuse and neglect of helpless children, and their separation from powerless families and communities. The legacy of Indian Residential Schools has contributed to social problems that continue to exist in many communities today. It has taken extraordinary courage for the thousands of survivors that have come forward to speak publicly about the abuse they suffered. It is a testament to their resilience as individuals and to the strength of their cultures. Regrettably, many former students are not with us today and died never having received a full apology from the Government of Canada. The government recognizes that the absence of an apology has been an impediment to healing and reconciliation. Therefore, on behalf of the Government of Canada and all Canadians, I stand before you, in this Chamber so central to our life as a country, to apologize to Aboriginal peoples for Canada’s role in the Indian Residential Schools system. To the approximately 80,000 living former students, and all family members and communities, the Government of Canada now recognizes that it was wrong to forcibly remove children from their homes and we apologize for having done this. We now recognize that it was wrong to separate children from rich and vibrant cultures and traditions that it created a void in many lives and communities, and we apologize for having done this. We now recognize that, in separating children from their families, we undermined the ability of many to adequately parent their own children and sowed the seeds for generations to follow, and we apologize for having done this. We now recognize that, far too often, these institutions gave rise to abuse or neglect and were inadequately controlled, and we apologize for failing to protect you. Not only did you suffer these abuses as children, but as you became parents, you were powerless to protect your own children from suffering the same experience, and for this we are sorry. The burden of this experience has been on your shoulders for far too long. The burden is properly ours as a Government, and as a country. There is no place in Canada for the attitudes that inspired the Indian Residential Schools system to ever prevail again. You have been working on recovering from this experience for a long time and in a very real sense, we are now joining you on this journey. The Government of Canada sincerely apologizes and asks the forgiveness of the Aboriginal peoples of this country for failing them so profoundly. We are sorry. In moving towards healing, reconciliation and resolution of the sad legacy of Indian Residential Schools, implementation of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement began on September 19, 2007. Years of work by survivors, communities, and Aboriginal organizations culminated in an agreement that gives us a new beginning and an opportunity to move forward together in partnership. A cornerstone of the Settlement Agreement is the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This Commission presents a unique opportunity to educate all Canadians on the Indian Residential Schools system. It will be a positive step in forging a new relationship between Aboriginal peoples and other Canadians, a relationship based on the knowledge of our shared history, a respect for each other and a desire to move forward together with a renewed understanding that strong families, strong communities and vibrant cultures and traditions will contribute to a stronger Canada for all of us. God bless all of you. God bless our land.” |

| RESPONSES

Note from Thunderbird: Even though the apology was finally a reality, it was another fight on the part of Indigenous people to be allowed to respond in the House of Commons. Harper had denied this right, saying only opposition leaders could respond. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed and Native representatives were allowed to have a voice. On the most important day in modern Indigenous history, our voices were once again nearly silenced. An apology is just an apology, without redemption, true healing cannot take place. Watch this riveting video with Winona La Duke, Anishinaabe Activist and Speaker

|

| A DAY, AND A DECADE, LATER: WHAT HAS CHANGED FOR US by Kevin D. Annett I awoke this morning to the same familiar sounds of east Hastings street, as birdsong was smothered by traffic’s din – a day after a government “apology”, and a decade after a Tribunal that started everything. Faces have come and gone in one day, and in thirty six hundred, but the same cold reality stared back at me today in the hard eyes of angry desperation of the men and women, mostly aboriginal, who share these streets, and who never rest. Steven Harper said “I’m sorry” to these people yesterday, but he didn’t look sorry as he lectured the gala throngs on Parliament Hill about the Indian residential schools. He didn’t look outraged, either, as he spoke about children being ripped forever from their homes and way of life. Nor, for that matter, did any other politician who spoke to the carefully arranged crowd of natives and whites. But there was plenty of sorrow and outrage on our streets yesterday. Somebody else had just died, a native man named Vince who had, naturally, been jailed in residential school as a kid and suffered horribly there, and every day of his life thereafter. The clusters of people who camp around Main and Hastings were discussing Vince yesterday, rather than shuffling off obediently to the official viewings of Steven Harper’s “apology” arranged by the government’s flunky native chiefs. “That’s one less Indian problem for the fuckers” commented Bingo, a homeless native guy who is always at the forefront of our protests outside the Catholic church that killed Vince. “All their nice words don’t mean crap. Maybe to them they do but hey, it’s always been like that, right?” Right. As much as Steven Harper and his friends know nothing of Bingo and Vince, they could not have spoken in Parliament yesterday and garnered such undeserved praise without the two of them, and all the other suffering throngs on every mean street across Canada that residential school survivors call home. Yesterday’s Parliamentary extravaganza, in fact, was built entirely on the efforts and revelations of these survivors that began ten years ago today, in a union hall in the east end of Vancouver. It was called the North West Tribunal into Canadian Residential Schools, and it was sponsored by a United Nations affiliate called IHRAAM. Early that spring of 1998, the late Harriett Nahanee and I invited IHRAAM to come and listen to the stories of the residential school survivors who we had been working with for two years, many of whom had – like Harriett – witnessed killings and burials of fellow students at the schools. From June 12 to 14, twelve IHRAAM judges and a UN observer heard stories of murder, torture, involuntary sterilization and medical experimentation in west coast residential schools, from eyewitnesses: people like Belvy Breber, Dennis Charlie, Elmer Azak and Ed Martin. Exactly one reporter showed up to the event – the Globe and Mail ran a short piece about the Tribunal on June 20, 1998 – but the Tribunal was an historic first: the only independent attempt ever to document deliberate genocide by the government and churches of Canada. This single event was responsible for all of the changes and gains that have been won for survivors in the past decade, including yesterday’s acknowledgment by a head of state that children did indeed die in church-run Indian residential schools in Canada. The Aboriginal Healing Fund, the first court settlements, and the Liberal government’s 1999 “apology” to survivors all occurred less than a year after our Tribunal. And yet, like Bingo and Vince, the IHRAAM Tribunal is officially ignored, and for the same reason: it does not fit into the government’s plan of containment and concealment that was so evident yesterday in the House of Commons. That plan is quite simple: to reduce the fact of genocide and mass murder to an accommodated issue of “abuse” that can be “resolved” with certain words and payments – and, in the process, to absolve the churches responsible for the crime from any responsibility for it. A simple plan, but a potentially explosive one because of two threats: the spectre of lawsuits and scandal as more survivors came forward in the wake of the IHRAAM Tribunal; and the appearance of first my book Hidden from History: The Canadian Holocaust, spawned by the Tribunal, and then, last year, my documentary film UNREPENTANT, whose release prompted the raising of the issue of disappeared residential school children in Parliament in April, 2007. Inspector Peter Montague of the RCMP is even more complimentary towards me. The chief smear artist of the covert operations branch of the RCMP in B.C., Montague engineered the public relations disaster known as the Gustafson Lake standoff, when unarmed Shuswap natives were assaulted by military vehicles and 77,000 rounds of fire from RCMP officers. Oddly, Montague was then assigned to the residential schools issue in 1996, after the first lawsuits began against his employer and the United Church of Canada. Montague sent a number of undercover agents into our IHRAAM Tribunal, two of whom are still busy smearing me all over the world. But to one of these agents, who subsequently spilled the beans, Montague said, “Kevin Annett is the one to worry about … Discredit him and you discredit the issue.” (spring, 1999) It’s strangely reassuring to see how so very little has changed in the past decade, which figures, considering how much the churches and government have to lose if they ever had to actually face the music over all those kids they killed in their residential schools. Still today, the official organs of church, state and mass media in Canada seem haunted and obsessed by me, as if I am the issue; as if I personify the massively guilty conscience of “white” Canada. That guilt struggled to be assuaged yesterday in Parliament, and in the media orgasm that tries to convince us that the “issue” of residential schools is finally resolved. But it cannot be alleviated, any more than can the pain of Bingo, or Vince. We are, all of us, quite missing the point: namely, that one cannot “apologize” for or resolve that which we do not understand. To comprehend the horror and fact of the residential schools requires that we look first and last at ourselves, as we truly are: as part of a Thing that has spawned not only genocide, but planetary ecocide. Holding up such a mirror to that truth and to my own culture has been my sole waking purpose for the past thirteen years. And, thankfully, I have witnessed over those years an amazing thing: the official wall of denial has begun to crumble, despite all the King’s horses and all the King’s men. Last year, it would have been inconceivable for the Canadian media and government to be speaking almost casually about unmarked graves and dead residential school children. Yet now, even the National Post proclaims in its headlines, “Are Reconciliation and Truth Compatible?” (a slogan I’ve used for years now); and it’s suddenly become fashionable for the press to play voyeuristically with tales of buried native children, while holding no-one in particularly accountable. More is being admitted, all the time, as the Thing’s mask slips. So don’t believe the Big Lie emanating from Ottawa yesterday. It’s all smoke and mirrors, designed to hide the crumbling tower of colonial Canada. Believe, instead, that Vince’s time of vindication is coming; and along with it is approaching a great and terrible judgment on those masters of Church and State who like to imagine they have gotten away with their crime. Ten years has taught me to stand aside from their world, as it topples. June 12, 2008 Kevin D. Annett is a community minister, film maker and author who lives and works in the downtown eastside of Vancouver, on occupied Squamish Nation territory. His website is: www.hiddenfromhistory.org |

| GLOBE AND MAIL – June 12, 2008

“I accept the Prime Minister’s apology” – Stephen Kaakfwi, Former Premier of the North West Territories and Residential School Survivor. “A century and a half ago, an imported government declared itself “Canada” – a strong aboriginal word. Almost immediately, it began the torturous process of destroying all other aspects of aboriginal culture and identity it did not value. The policy of assimilation through Indian residential schools is the most destructive example. Finally, Canada admits this shameful history. On Wednesday, the Prime Minister said sorry for the devastation caused to aboriginal children and families. He also asked for forgiveness. That message was no small mouthful. It took personal courage and political will to utter it. I know, because in 2002, as premier of the Northwest Territories, I offered my own apology to our residential school survivors. I did it despite resistance from the bureaucracy and my own ministers and colleagues. It was difficult and humiliating to face the survivors and their parents and children. I know what Stephen Harper and the other national party leaders must have been feeling on Wednesday. As a residential school survivor myself, I also understand the importance of the apology offered, and the strength and courage it will take survivors to consider and accept it. At 9, I was sent to residential school. A nun shaved my head and stripped me bare in front of all the other boys, followed by months of repeated beatings, whippings, sexual abuse and solitary confinement in a dark, locked closet. Why? Because I was bad and deserved it. That’s what they said. But this is not just about me. It is about my father, brothers and sisters … and my 87-year-old mother. We always wondered why she never told stories of her family. Recently, she finally told us she was taken away at 6 and never returned home until she was 14. She left with baby teeth, and returned a young woman. Her family all died within five years. She has no childhood or family memory, no stories to tell. So many aboriginal brothers and sisters across the country have their own versions of this same sickening story. Twenty-five per cent of us did not survive residential schools. What a crippling loss to our peoples. Even in times of active warfare, Canada has never faced such a high death toll. Generations have been ruptured from each other. Lives have been shattered. Spirits have been broken. Our communities are haunted by so many of the living dead. I was lucky. I survived. Many survivors learned to fight, we had to. Over the past 30 years, every single gain for aboriginal peoples has been hard-fought. In school, we learned nothing about our histories and ourselves. We were told we had no rights. We were the last Canadians to get the vote, in 1960. Before then, to vote we had to give up our treaty rights. In the 1970s, it took a Supreme Court judge to say we had aboriginal rights for governments to listen! In the 1980s, during constitutional talks, governments begrudgingly referred to aboriginal rights as an “empty box” that could be filled with specific rights only if they agreed. Over and over in our history, the recognition, negotiation and implementation of our rights has consistently been met only with great reluctance. Is this the dramatic turning point we have all been fighting and praying for? The Prime Minister has said sorry to the First Peoples of this country. I don’t know exactly what motivated him. I imagine that political and legal factors were carefully weighed. Or is it because he understands what it is to be a father? Surely all parents can imagine the horror of having your children forcibly stolen as little more than babies, to return as young adults – strangers, who no longer speak your language. You completely missed their childhood … they did, too. Whatever the PM’s reasons, I hope the Canada he represents will now work with us to restore strong, healthy and vibrant families, communities and nations, not begrudgingly, but because it is the right thing to do. You offer an apology, which I accept. But that restoration work will deliver the forgiveness, which you also seek. This apology marks us all. It is the end of national denial, the beginning of truth. It opens us to the promise of new relationships. Making amends takes longer; it requires sustained commitment over time to heal wounds and return spirit and dignity to survivors and their families. Reconciliation, with action, can take us there. Together, we can work to make this the best place in the world for all who call Canada home. I am proud of this moment in Canada’s history. I accept the Prime Minister’s apology. It is what my father and grandfather would have done. We are about to write a new chapter of Canada’s history. Twenty-five years from now, may children across the land be proud of it, and proud also of all their grandparents, who today began a journey together to make things right. |

| EDMONTON SUN, GREG WESTON

A chilling wind stirred the magnificent autumn forests where the two rivers meet as the Dene Elders with faces etched deep gathered to witness the second coming of the Father of Fathers. It was September 1987, and Pope John Paul 11 was revisiting far northern community of Fort Simpson, a previous appearance three years before thwarted by fog. The Native Elders were among the more than 5,000 aboriginals who had traveled for days, some for weeks, mostly in rusting pickups, but many by canoe, all to catch a glimpse of the Pope. The more I talk to them the more I wondered why they had bothered. Almost everyone I interviewed had horror stories of Indian residential schools run by Roman Catholic missionaries and other churches. Through tears they talked of literally being torn away from their families as young children, isolated far away in church-run boarding schools, and subjected to years of emotions, physical and sexual abuse. “I was only six years old when the priests loaded me on a barge and sent me to mission school at Fort Providence,” one of them told me. “I didn’t see my parents for four years. A mother told me, “it was every parent’s nightmare. My children were taken away as little ones. I couldn’t hold them until they were teenagers.” Even when children were reunited with their families, they were divided by language and culture, the schools having forbidden all things Indian. All, over 160,000 helpless aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their homes put into this grotesque attempt at cultural engineering through assimilation — “to kill the Indian in the child,” as the saying went. In fact, it is believed thousands of the children actually died before they could see their moms and dads again. If the elders who gathered in Fort Simpson that autumn day were hoping for a papal apology, they didn’t get one. In fact, the pontiff praised the Catholic missionaries who “taught you to love and appreciate the spiritual and cultural treasures of your way of life.” Right. For over a century, the federal government was no better until victims of residential school abuse began turning to the courts in the 1990s, courageously sharing their horrific stories with all Canadians. In 1998, Jane Stewart, the then Liberal government’s Indian affairs minister, expressed “profound regret” over the past actions of the federal government. But it was a $2-billion legal settlement with residential school victims in 2005 that finally opened the way for whatbecame yesterday’s emotional national day of mea culpa. With clarity, class and a rare depth of emotion that brought him close to tears, Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered a full and profound apology for every aspect of the fiasco. In many ways, Harper was admitting the obvious: Who today would doubt that “it was wrong to forcibly remove children from their homes”? Or that “far too often, these institutions gave rise to abuse or neglect and were inadequately controlled”? But judging by the tears on the faces of those receiving the apology, the PM’s words were exactly what they had waited a lifetime to hear. The apology doesn’t suddenly cure the problems plaguing our aboriginal communities. |

| CANADIAN PRESS – SUE BAILEY

For three decades, Willie Blackwater suppressed the pain. At age 39, he released his torment when a compassionate RCMP officer named Al Franczak asked if he’d ever been sexually abused. What poured out was a horrific account of repeated rape and beatings 30 years earlier at the Port Alberni residential school on Vancouver Island. Blackwater’s courageous revelations, along with those of 17 other former students, helped seal some of the very first related criminal convictions against Arthur Henry Plint, a sadistic dormitory supervisor. They also bolstered the class-action claims that would ultimately lead to a massive compensation settlement and a historic apology to be offered Wednesday in Parliament. Blackwater will be in the House of Commons when the prime minister finally stands to atone on behalf of all Canadians for what so many terrorized, isolated children endured. Ottawa conceded 10 years ago that physical and sexual abuse in the defunct network of federally financed, church-run schools was rampant. But no prime minister has ever officially apologized. “I have a lot of mixed emotions,” Blackwater said. “I’m looking forward to it, yet fearing it due to maybe wrong wording or whatever. But I think it will be one of the humongous chapters in my life that will help bring completion to a lot of…my trauma – and the trauma I’ve inflicted on others – from the residential school legacy. It’s got to come from his heart,” Blackwater, now 53, said of Stephen Harper’s statement to be delivered as 10 native guests encircle him in the Commons. “That’s where we as aboriginals talk from, it’s from our heart. We will hear the difference.” His ailing grandmother, who cared for him when his own mother died while he was a toddler, was pressured by government officials to enrol him and his brothers in the school. Blackwater was swiftly singled out by Plint. He recalled how the potbellied, chain-smoking dorm supervisor awoke him in the night, saying he had an emergency phone call from his father. Blackwater would testify years later about how Plint led him into a bedroom behind his office. Plint forced him to perform oral sex and, days later, raped him, inflicting “the worst pain I ever felt in my life.” Those attacks would go on at least monthly for the next three years. When Blackwater sought help, he was beaten by Plint so badly it kept him quiet for the next 30 years. Franczak, who retired from the RCMP two years ago, first interviewed Blackwater as part of a task force researching the earliest reports of abuse at Port Alberni. “To this day I keep thinking how could we, as a society … allow this to happen? I don’t get it.” Daily parliamentary business has been called off for the apology beginning just after 3 p.m. ET, to be followed by opposition response but no statements from native leaders. Liberal MP Tina Keeper, a member of the Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba, led off Tuesday’s question period pleading with the Conservatives to reverse their contentious refusal to allow such reaction in the Commons. “For many aboriginal people, the apology tomorrow will be one of the most emotional moments of their lives,” she said in a rare turn for a backbench MP as lead questioner. “But they must not be voiceless.” Harper inspired catcalls from the opposition benches, citing parliamentary tradition for his refusal to allow immediate aboriginal comment for the official record. He further advised rival parties not to “play politics” with the somber event. Indian Affairs Minister Chuck Strahl urged Keeper to treat the apology with the “gravitas it deserves.” Assembly of First Nations National Chief, Phil Fontaine, who has spoken publicly of his own sexual abuse in residential school, was still hoping Tuesday that Harper would change his mind. Nonetheless, he put a bright face on what has been a tense several days of negotiations with a government accused of not treating the apology with the respect required.” |

| Julie Marion was outside the Centre Block to hear the apology. Her mother and aunts all attended residential schools. Ms. Marion, dressed in traditional regalia, said there was no one willing to teach her the ways of her Mi’kmaq culture and she was warned as a child not to tell people she was Indian. She was forced to learn the traditions herself as an adult. “It has been a very long time that the elders have been waiting for this,” she said quietly. “I am surprised that they are actually telling the truth about some of the things that have happened.” |

| EXCERPT FROM THE LOS ANGELES TIMES

Geraldine Maness-Robertson, 72, a Chippewa from Aamjiwnaang First Nation, said her six years at an Anglican school were a “horrific experience,” and her hands were often whipped with a razor strap to break her spirit. “When I left, I was so full of rage and anger and hatred,” she said. “Today’s apology was so helpful, it hit all the areas of hurt. I have spent my whole life reconciling, and I turned a page today.” Canada got it right, said Sammy Toineeta, a founder of the Boarding School Healing Project, a national coalition seeking justice for similar abuses and loss of culture in Native American boarding schools in the United States. “An apology does not carry much weight unless there is something behind it. In Canada, they got a certain amount of land and money, and then the apology,” said Toineeta, a Lakota who attended a boarding school in Rosebud, S.D. “That’s the way to do it. Action first and then words. |

|

CHOOSING TO LIVE “Residential School survivors made a choice to save their own lives; probably the bravest thing one person could do. My mother survived. Sometimes events, like the horrors of residential school are imposed; the choice occurs when the individual decides to live or not.” Gandoox, Coast Tsimshian Elder |

|

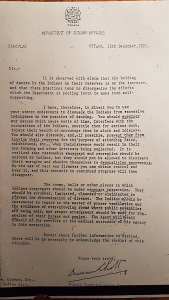

THREE OF THE MOST HENOUS ENEMIES OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLE

“When the school is on the reserve, the child lives with its parents, who are savages, and though he may learn to read and write, his habits and training mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly impressed upon myself, as head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.” 1879 It is hoped that a system may be adopted which will have the effect of accustoming the Indians to the modes of government prevalent in the white communities surrounding them, and that it will thus tend to prepare them for earlier amalgamation with the general population of the country.” 1880 “The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as they are fit to change.” 1887 “The third clause provides that celebrating the “Potlatch” is a misdemeanour. This Indian festival is debauchery of the worst kind, and the departmental officers and all clergymen unite in affirming that it is absolutely necessary to put this practice down.” 1894 |

EGERTON RYERSON, (1803-1882) EGERTON RYERSON, (1803-1882)

“Peter Jones and myself attended the great annual meeting of the Indians, and opened the Gospel Mission among them. In my first address, which was interpreted by Peter Jones, I explained to the assembled Indians the cause of their poverty, misery, and wretchedness, as resulting from their having offended the Great Being who created them, but who still loved them so much as to send His Son to save them, and to give them new hearts, that they might forsake their bad ways, be sober and industrious; not quarrel, but love one another, & I contrasted the superiority of the religion we brought to them over that of those who used images.” (Quote from Next page). “It is of the last importance to perpetuate and extend the impressions which have already been made on the minds of these Indians. The schools and religious instruction must be continued; and the Gospel must be sent to tribes still in a heathen state. Egerton Ryerson, Diary Entries (1827) when he was appointed Missionary to the River Credit Native people (Lake Simcoe) – He is sometimes referred to as the Father of Residential Schools. In 1955, McLean’s Magazine dubbed him the “Gloomy Renegade”. |

| STRUCTURE: THE INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL “If you are on Highway 104 in a Scubenacadie town Mi’Kmaq Poet, Rita Joe, We are the Dreamers: Recent and Early Poetry. Wreck Cove, NS, Breton Books, 1999. |

| “You will not give up your idle, roving habits to enable your children to receive instruction. It has therefore been determined that your children shall be sent to schools where they will forget their Indian habits and be instructed in all the necessary arts of civilized life and become one with your white brethren.” (Indian Superintendent, P.G. Anderson, 1846, Sing The Brave Song, J. Ennamorato, pg. 53.), “If these schools are to succeed, we must not have them near the bands; in order to educate the children properly we must separate them from their families. Some people may say that this is hard, but if we want to civilize them we must do that.” (A federal cabinet minister, 1883, in J. R. Miller, Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: History of Indian-White Relations in Canada, 1989, pg. 298. |

| KILL THE INDIAN AND NOT THE CHILD

1909, Dr. Peter Bryce, general medical superintendent for Indian Affairs reported to the Ministry that between 1894-1908 the mortality rate in western Canadian residential schools was between 35%-60%! The statistic became public in 1922. Dr. Bryce retired from his position in DIA and wrote a book, The Story of a National Crime: Being a Record of the Health Conditions of the Indians of Canada from 1904 to 1921. He also alleged in his book that he felt the high death rate was deliberate because healthy children had been exposed to diseases such as tuberculosis. In the early 1920s another doctor, F.A. Corbett while working in Alberta, found similar startling statistics at various residential schools, including, Hobbema, and Sarcee. At Sarcee, only four children from over thirty did not have tuberculosis. Moreover, with such a high illness and near death rate, the children still had to attend classes, because their illnesses were not a priority. As history shows these public-record tragedies caused barely a ripple on the collective Canadian conscience. |

| THE WAY IT USED TO BE

“The traditional way of education was by example, experience, and storytelling. The first principle involved was total respect and acceptance of the one to be taught, and that learning was a continuous process from birth to death. It was total continuity without interruption. Its nature was like a fountain that gives many colours and flavours of water and that whoever chose could drink as much or as little as they wanted to whenever they wished. The teaching strictly adhered to the sacredness of life whether of humans, animals or plants.” |

| WHAT THE INDIGENOUS LEADERS WANTED

“Taking into consideration the high cost of assimilation through education, and deciding the process was too lengthy and expensive to continue, the government failed to provide adequate funds to fulfill the treaty promises. The omission resulted in heated debates between the Church and State over who would fund the construction and operation of Indian schools. Canada’s government and various churches, which by now were tiring of Indians, schools and their government partners, agreed on financial contracts. Since the missionaries were still the cheapest educators in the country, Indian education remained in their hands for almost 100 years following the signing of treaties.” WHAT NATIVE LEADERS WANTED: The setting up of residential schools was to say the least a clash of two cultures. Whereas a number of Chiefs wanted white education for their children, their reasons differed dramatically from the government’s reasons. They wanted European education so that their children would be able to survive in a rapidly changing new world. Native leaders were firm in not wanting to assimilate their children into white culture in order to receive that education; nor was the intent to surrender their lands and to deliver their children into forcible confinement far away from their families and traditional cultures their goal. In other words, they made it very clear they desired only education for their offspring, not a fundamental change in their way of life. Native people were victims; they did not willingly agree to Canada’s deeply oppressive apartheid policies against its First Citizens. They did not willingly agree to Indian Agents luring their children away with promises of rides in planes. Who in their right mind would?? For decades, the appalling lie that Native Leaders demanded the residential schools for their children was perpetuated. In other words, Church and State tried their best to “spin-doctor” their involvement by trying to place the responsibility for the debacle squarely on the shoulders of Indigenous leaders. All Native leaders wanted was education for their offspring, not a fundamental change in their way of life. WHAT NATIVE PEOPLE GOT: The wishes of Native leaders were ignored and the exact opposite occurred. A misguided Church and State led by Canada’s extremely racist government leaders, endeavouring to civilize the ‘savages’ in the ways of the Europeans, combined to create a diabolical set of circumstances that from the outset were doomed to failure. Poorly paid and morally bankrupt student teachers and missionaries, who were at best barely functional illiterates, were put in charge of educating Native children. In fact, thousands of children between 1880-1988 were exposed to kidnapping, unimaginable physical and sexual abuse, starvation and virtual slavery that until recently had been Canada’s dirty little secret. The Residential School debacle reached its zenith in 1931 (see time line below). The savagery, however, continued for decades leaving physical, emotional, mental and spiritual scars that reverberate to this day. As a direct result of this horror, at the present time, alcohol and drug abuse among Native people is five times the national average; sexual and family abuse eight times the national average; suicide rate among Native teens five times the national average. “Sometimes my tears were brought on by desperate longings to be home. At other times, I cried because of Sister Superior’s sadistic punishments which she arbitrarily inflicted on those of us who spoke out of turn…,or showed disrespect…by asking for proof of the existence [of God[….And on other occasions, I cried because I was terrified by the footsteps that regularly crept up the fire escape to our dorm. Those nights I’d jump in bed with my sister, Carla. As we clung to one another for protections, we’d hear frantic whisperings, and moaning over top of crying. Years later I became convinced that poor little girls were being sexual victimized.” SEE TIME LINE BELOW |

THE STRUCTURE OF RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS

| The four main churches responsible had a variety of things in common when it came to the infrastructure of the prisons.

“All aspects of First Nations culture were eliminated from the schools. Children were forbidden to speak their native language and were punished for doing so. Boys were segregated from girls, and siblings were intentionally separated in an effort to weaken family ties. Children were required to wear school uniforms instead of traditional clothing. Hairstyles were cut short in European style. The children ate primarily Euro-Canadian food.” (if they ate at all). It was not the intent to scholastically educate the children, but, rather, teach them menial tasks so they could potentially acquire positions as scivvies, maids, labourers. Therefore, upon release most children were lucky if they achieved barely a Grade 5-6 education. Also, during summer breaks or other so-called vacations, children were forced to billet with white families “in order to prevent them from renewing cultural connections with their families.” (Roberts, Ibid,) |

| “Indians sometimes think that if government authorities became convinced they could solve the Indian problem by purchasing gallons of white paint and painting all of us white, they would not hesitate to try. In fact, the government’s education policy almost seems aimed in that direction. Indians recognize that education is one of the major tools that will help us strike off the shackles of poverty and, incidentally, the tyranny of government direction. But the white man apparently believes that education is a tool for the implementation of his design of assimilation.” (Cardinal, Harold, The Unjust Society, pg.51) |

FEDERAL MANDATE

| “I want to get rid of the Indian problem…Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question and no Indian department.” (Duncan Campbell Scott) |

Nicholas Flood Davin Report of 1879 noted that “the industrial school is the principal feature of the policy known as that of ‘aggressive civilization’….Indian culture is a contradiction in terms…they are uncivilized…the aim of education is to destroy the Indian.” |

| “It is readily acknowledged that Indian children lose their natural resistance to illness by habituating so closely in the residential schools and that they die at a much higher rate than in their villages. But this does not justify a change in the policy of this Department which is geared towards a final solution of our Indian Problem.” (Duncan Campbell Scott) |

“The federal government and the churches – Anglican, Roman Catholic, Methodist and Presbyterian — applied to their ‘Indian Problem’ the instrument of education…which…focused on labour skills….” (The Healing Update Has Begun from the Aboriginal Healing Foundation, May 2002) |

RESULTS OF FEDERAL MANDATE: INCALCULABLE ATROCITIES

| Children were kidnapped and taken long distances from their communities in order to attend school. Once there, they were held captive, isolated from their families of origin, and forcibly stripped of their language, religion, traditions and culture. Many Native children grew up with little knowledge of their original culture. Being forced to live with no culture resulted in high suicide rates, difficulties with parenting, drug and alcohol problems, family abuse.

“Then there are testimonies of hundreds of former students whose list of abuses includes kidnapping, sexual abuse, beatings, needles pushed through tongues as punishment for speaking Indigenous languages, forced wearing of soiled underwear on the head or wet bed sheets on the body, faces rubbed in human excrement, forced eating of rotten and/or maggot infested food, being stripped naked and ridiculed in front of other students, forced to stand upright for several hours — on two feet and sometimes one — until collapsing, immersion in ice water, hair ripped from heads, use of students in eugenics and medical experiments, bondage and confinement in closets without food or water, application of electric shocks, forced to sleep outside or to walk barefoot in winter, forced labour and on and on.” |

IN THE WORDS OF THE SURVIVORS

| “When I was growing up, when I was in the residential schools, I was lost for a very long time….I didn’t hear the drum beat, I heard the organ. It took me 36 years to find out who I am.” (AHF Regional Gathering Participant, November 9, 2000) |

“It is very difficult to come and deal with these things to address your healing journey. We need more time, 10 years will not be enough. It takes generations for corrections to be made.” (AHF Regional Gathering Participant, November 9, 2000) |

HISTORY OF CANADA’S RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL SYSTEM: TIMELINE

| 1930 – Indian Residential School, Shubenacadie, NS. Photograph: Elsie Charles Basque. Collection of Dr. Elsie Charles Basque. Copy photo: Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax

The abuse of Native children was so widespread, over such a long period of time, that as the timeline shows, Canada’s attempts to eliminate Native Nations is now embedded in the general history of the country. Payments as a result of class-action lawsuits for these atrocities against an innocent people could exceed the billion dollar mark for both States and Churches. Money, however, can never make up for the incalculable cost in human life, emotional, physical, mental and spiritual suffering and loss of Indigenous cultural knowledge and practices. |

| Prior to 1840s | There was no educational policy as the government had little interest in the education of Natives. There were, however, a handful of schools run by representatives of missionary organizations, and a few boarding schools were established in Ontario. The schools were supervised by ill-trained and poorly paid missionaries. Last on their list of priorities was addressing the low attendance and academic progress of their Native students. The residential school had been contrived specifically to enable missionaries to meddle with the character formation and identity of Native children even though the parents had stressed repeatedly that they wanted education, not assimilation. |

| Bagot Commission set up in 1842 by Governor Sir Charles Bagot | He asserted “after a two-year review of reserve conditions, that communities were get only in a “half-civilized state.” (Report of the Affairs of Indians in Canada, Journals of the Legislate assembly on the Province of Canada, 1844) – taken from John Milloy’s, A National Crime, pg. 12.”The Bagot Commission began the formulations that brought forward the assimilative policy and eventually the residential school system. The central rationale of the Commission’s findings was that further progress by communities would be realized only if the civilizing system was amended to imbue Aboriginal people with the primarily characteristics of civilization: industry and knowledge.” Milloy, pg. 13. |

| 1844 | “Bagot Commission published their recommendations with two very influential supporters of residential education. Lord Elgin, the “Father of Responsible Government,…The Reverend Egerton Ryerson, the Superintendent of Education for Upper Canada.” (Milloy, pg. 15) |

| 1844 | “I suggest they be called industrial schools….I understand them not to contemplate anything more in respect to intellectual training than to give a plain English education adapted to the working farmer and mechanic…, but in addition to this, pupils…are to be taught agriculture, kitchen, gardening and mechanics so far as mechanics is concerned with making and repairing the most useful agricultural equipment.”Ryerson believed that “Indians were best suited to being working farmers and agricultural labourers.” (Milloy, pg. 16) |

| 1840s | First residential schools opened in Upper Canada (Ontario). The federal government became involved after the results of the results of the Bagot Commission of 1842 were published, and the Gradual Civilization Act of 1857 was enacted. These documents paved the way for the establishment of government funded schools that would teach the Natives English and hopefully eliminate the Native culture. |

| 1847 | “There is a need to raise the Indians to the level of the whites…and take control of land out of Indians hands. The Indian must remain under the control of the Federal Crown rather than provincial authority, that effort to Christianize the Indians and settle them in communities be continued,….that schools, preferably manual labour ones, be established under the guidance of missionaries.…Their education must consist not merely training of the mind, but of a weaning from the habits and feelings of their ancestors, and the acquirements of the language, art and customs of civilized life.”

(Excerpt from a report on the study of Native education commissioned by the Assistant Superintendent General of Indian Affairs. It would form the basis for future directions in policy for Indian education and how the residential schools were to be run in Ontario.) NOTE: Although the report containing the above quote appears to be common knowledge, there does not seem to be an actual publication of it. Even the Ryerson University archives does not have it. If any gentle reader can offer enlightenment, send an email. |

| 1857 | Gradual Civilization Act applied to all Indians in the Province of Canada; they were an affirmation of legislative control over Indians. The legislation stated it was shouldering the responsibility and authority to define who was an Indian as a preliminary to making it feasible for the Indian to cease being an Indian. Part of the process was forcing Native children into government-run schools. |

| 1876 | Indian Act gave further responsibility to the federal government for Native education. |

| 1883 | Canadian Federal Government builds RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS also called Industrial Schools far away from reserves to ensure children would be educated in European ways, without parental or cultural influence – Sir Hector Langevin preaches that, “if these schools are to succeed [in terms of integration] we must not place them too near the bands; in order to educate the children properly we must separate them from their families.” (J. Ennamorato, Sing The Brave Song, pg. 47) |

| 1879 | “Kill the Indian and Save the Man,” was the motto coined by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, who founded the first Native American Boarding School, Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania and was the architect of Native education and federal Native policy. The purpose of the Native American Boarding schools was to assimilate Native American children into the American culture by placing them in institutions where they were forced to reject their Native American culture. |

| There was considerable denominational rivalry among the Anglican, Catholic, Methodist and Presbyterian churches. One Anglican referred to the Ojibwa as biased: “Their prejudices are so much warped in favour of the Catholics….they received the crucifix, beads and other mummeries…[and] instead of the gospel…they pray in the same manner as they formerly did to their medicine bags.” (J. Ennamorato, Sing the Brave Song, Pg. 73) | |

| Mid- 1880s | REMOVING Native children from the home and villages to be instructed in Christianity is now well established. More often than not children were kidnapped without the knowledge of the parents. The bulk of the “educational experience” in the schools, however, was manual labour rather than scholastic. Children worked mostly in the fields, laundries or shops (a concept borrowed from the United States Residential School System) and barely had a grade six education by the time they were released.

Sexual perversions of the most heinous kinds at the hands of priests and nuns were commonplace, spiritually and emotionally damaging generations of Indigenous children. We are still paying for these atrocities to the present day with family and substance abuse five times the national average. |

| 1892 | An order-in-council was passed in 1892 announcing the regulations for the operation of residential schools. It set up a grant arrangement stating that the government would give $110-$145 per student per year to the church-run schools and $72 per student in the day schools. Little of this money actually went into hiring competent, compassionate and literate teachers. |

| 1910 | Ontario Public School History of Canada: “All Indians were superstitious, having strange ideas about nature. They thought that birds, beasts….were like men. Thus an Indian has been known to make a long speech of apology to a wounded bear. Such were the people whom the pioneers of our own race found lording it over the North American continent – this untamed savage of the forest who could not bring himself to submit to the restraints of European life.” |

| 1914-1918 | New amendments to the Indian Act which made it easier for the government to obtain convictions for “spiritual mis-behaviour. |

| 1931 | Number of Schools peaks: Eighty schools: one in Nova Scotia, thirteen in Ontario, ten in Manitoba, fourteen in Saskatchewan, twenty in Alberta, sixteen in British Columbia, four in the Northwest Territories, and two in the Yukon. In addition, two schools are planned for Quebec. Note: Many residential schools were built on flat land and in remote areas (prairies) making escape difficult; children could be seen for miles, hunted down and brought back by the Indian Agents. |

| 1940s | 8,000 Indian children, half the student population were enrolled in seventy-six residential schools across the country. In 1930, three-quarters of Indian students were in grades one to three, and only three in every hundred students progressed past grade six.

Students were discouraged by school officials to go on to higher grades and were often ordered out of the school by age sixteen. At a residential school in northwestern Ontario, a federal inspector admonished the administrator for offering grades nine, by saying, “If we let the Indian people go to grade nine then they’ll want to go to grade ten, and then they’ll want to go to university, that’s what we don’t want.” |

| Education of Girls | Girls were educated because it was thought that if Native male residential school graduates married unschooled Native females they would simply revert back to their prior ‘heathenism’. (Also called, ‘The Blame it on Eve for Everything Syndrome!’) |

| Late 1950s | Focus begins to shift. Understatement of the century: Residential schools were not accomplishing their purpose of cultural assimilation and some thought that the Natives should not be taught to compete with whites but should be taught to make a living on the reserve. The DIA begins to phase out the residential schools because they realized a new approach was needed towards Natives. Drug and alcohol abuse were on the rise and were directly attributed to the appalling conditions, sexual abuse and slavery endured by Native captives. |

| 1996 | Last federally-operated residential school is closed (Akaitcho Hall in Yellowknife). It is estimated that more than 100,000 Native children aged six and up attended the national network of residential schools from 1930 until the last one closed. |

| 1990’s | “More than 4,500 lawsuits have been launched representing at least 9,000 claimants who allege physical or sexual abuse in the now defunct schools run by Catholic, Anglican, United and Presbyterian church groups for the government. The suits threaten the financial viability of some of the Churches. For example: “Government and Church organizations, including the St. Paul Diocese, are facing up to $195 million in damages in lawsuits filed on behalf of 230 former Native students of the Blue Quills Residential School.

The suit also names the Oblates, the Grey Nuns, the Attorney General of Canada and the Roman Catholic Church as defendants. It alleges that Native people suffered abuse and, “brutal, inhumane and cruel treatment” while they were students at the school in St. Paul. While many of the allegations contained in the court documents are of a general nature, more than 20 individuals, both lay and religious, are named in connection with specific allegations.” By Jay Charland, Staff Writer Edmonton. |

| 1993 – August 6 APOLOGY |

Anglican Archbishop, Michael Peers issues an apology on behalf of the United Church, to the National Native Convocation in Minaki, Ont., Friday, Aug. 6, 1993. He had spent several days listening to the pain and brokenness of Native people.

“I have felt shame and humiliation as I have heard of the suffering inflicted by my people, and as I think of the part our church played in that suffering. I am deeply conscious of the sacredness of the stories that I have heard and I hold in the highest honour those who have told them. I am sorry more than I can say that we were part of a system which took you and your children from home and family. I am sorry more than I can say that we tried to remake you in our image by taking from you your language, and your signs of identity. I know how often you have heard words which have been empty because they have not been accompanied by actions. I pledge to you my best efforts, and our church at the national level to walk with you on the path of God’s healing.” The apology was accepted on behalf of those present by Elder, Vi Smith. The grace showed by the Indigenous people in their forgiveness lifted the church from bended knee. Now it is up to both parties to try and walk together. |

| 1996 | The Royal Commission Report on Aboriginal People is released. It is a far-reaching, comprehensive message of reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Part of the breakdown in this relationship, is described in the RCAP report as the cultural superiority and policy of assimilation that finds expression in the Indian Residential Schools. The report is a sweeping condemnation of the attitudes and behaviour of the federal government. It suggests major reforms which to this day have been largely ignored by the Federal Government.

Very little of this report was acted on despite intense lobbying by Native groups. |

| January 8, 1998

LET’S RECONCILE! Canadian Government |

The Canadian Government through the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs apologized to the country’s 1.5 million Indigenous people for decades of mistreatment that include attempts to stamp out Native culture and assimilate Indians and mixed race people. Minister of Indian Affairs Jane Stewart reads a ”Statement of Reconciliation” that acknowledges the damage done to the Native population – including the hanging of Louis Riel after he led a rebellion of Indian and mixed-race people in western Canada in 1885. The government apology stops short of pardoning Riel, something Indigenous leaders have demanded for decades. Stewart does, however, apologize for the government’s assimilation policies.

”Attitudes of racial and cultural superiority led to a suppression of aboriginal culture and values,” she says. ”As a country, we are burdened by past actions that resulted in weakening the identity of aboriginal peoples, suppressing their languages and cultures, and outlawing spiritual practices. We must recognize the impact of these actions on the once self-sustaining nations that were dis-aggregated, disrupted, limited or even destroyed by the dispossession of traditional territory, by the relocation of aboriginal people, and by some provisions of the Indian Act. The time has come to state formally that the days of paternalism and disrespect are behind us and we are committed to changing the nature of the relationship between aboriginal and non-aboriginal people in Canada.” A $350 million dollar Healing Fund is created. Most First Nations do not believe that this sum is anywhere close to compensating them for the damage to Native societies; the money does not include off-reserve Natives, Inuit or Métis. To date, little of the money has found its way into the hands of the survivors. NOTE: Although it was referred to as Canada Apologizes, the apology was not given by the chief representative of the government, the Prime Minister. This is significant. If he had, it would have been an admission of culpability and the lawsuit settlements would have skyrocketed. Money? The hearts and healing of the Original People? Money? The hearts and healing of the Original People? – Money won. |

| 1998 – APOLOGY from the United Church of Canada | “From the deepest reaches of your memories, you have shared with us your stories of suffering from our church’s involvement in the operation of Indian Residential Schools. You have shared the personal and historic pain that you still bear, and you have been vulnerable yet again. You have also shared with us your strength and wisdom born of the life-giving dignity of your communities and traditions and your stories of survival.

In response to our church’s commitment to repentance, I spoke these words of apology on behalf of the General Council Executive on Tuesday, October 27, 1998: “As Moderator of The United Church of Canada, I wish to speak the words that many people have wanted to hear for a very long time. On behalf of The United Church of Canada, I apologize for the pain and suffering that our church’s involvement in the Indian Residential School system has caused. We are aware of some of the damage that this cruel and ill-conceived system of assimilation has perpetrated on Canada’s First Nations peoples. For this we are truly and most humbly sorry. To those individuals who were physically, sexually, and mentally abused as students of the Indian Residential Schools in which The United Church of Canada was involved, I offer you our most sincere apology. You did nothing wrong. You were and are the victims of evil acts that cannot under any circumstances be justified or excused. We know that many within our church will still not understand why each of us must bear the scar, the blame for this horrendous period in Canadian history. But the truth is, we are the bearers of many blessings from our ancestors, and therefore, we must also bear their burdens.” Our burdens include dishonouring the depths of the struggles of First Nations peoples and the richness of your gifts. We seek God’s forgiveness and healing grace as we take steps toward building respectful, compassionate, and loving relationships with First Nations peoples. We are in the midst of a long and painful journey as we reflect on the cries that we did not or would not hear, and how we have behaved as a church. As we travel this difficult road of repentance, reconciliation, and healing, we commit ourselves to work toward ensuring that we will never again use our power as a church to hurt others with attitudes of racial and spiritual superiority. We pray that you will hear the sincerity of our words today and that you will witness the living out of our apology in our actions in the future.” The Right Rev. Bill Phipps |

| 10 July 1999 – Front page of the Globe and Mail, Erin Anderssen, Reporter | Lawyers swoop in to cash on Native claims. Leaders worry the suffering of residential school victims is exploited by fees as high as 40%of awards. The article is about how the burgeoning industry for Canada’s legal profession, with a lot of money to be made. Specifically the article deals with the Peigan First Nation…the article continues on A7 under the title, “Some lawyers cashing in, Natives say the article says that the Law Society of Saskatchewan has passed a new ruling…that prevents its members from holding meeting in communities unless they are invited by prospective clients, and requires them to mark all documents sent to solicit business as “advertising material”. Forbids lawyers to settle fee arrangements until they meet with each client. |

| May 28, 2000 – Anglican Church | Archbishop Michael Peers issues a pastoral letter: “Resulting from abuse in the residential schools there are over 1,600 claims of varying kinds brought against the General Synod of the Anglican Church of Canada. About one hundred cases involve proven abuse of children, with the perpetrators given prison sentences. The costs of litigation and settlements for these alone is sufficient to exhaust all the assets of the General Synod and of some dioceses involved.” The Anglican Church may have to declare bankruptcy. Not going to happen as a result of a deal struck between the Church and the State which limits the amount of compensation to survivors! |

| March, 2001 – Federal government names The General Synod of the Anglican Church by third party action in 386 residential school cases. Similarly, the government also involves a number of Roman Catholic dioceses in residential school abuse trials, even though residential schools were operated by separately incorporated Orders within the church.

August, 2001 – Assembly of First Nations Chief Matthew Coon Come attended the United Nations World Conference Against Racism in South Africa. He embarrassed the Canadian government by telling delegates of the hundreds of years of suffering Native people have experienced at the hands of the Canadian government. Unrepentant Coon Come says, “I was not there to paint a rosy picture. That is not my job.” Six weeks later, in retaliation, DIAND Minister, Robert Nault slashed the AFNs budget from twenty-one million dollars to ten million dollars, causing the layoff of over seventy employees. Matthew Coon Come is no longer a hero to the federal liberals. 2002 – The Presbyterian Church and the federal government have agreed to terms that limit the church’s liability for residential lawsuits to $2.1 million. The agreement paves the way for settling outstanding claims by former students who were abused. |

|

| WASHINGTON APOLOGIZES September 9, 2000 |

The head of the Federal Bureau of Indian Affairs formally apologized yesterday for the agency’s “legacy of racism and inhumanity” that included massacres, relocations and the destruction of Indian languages and cultures.

‘By accepting this legacy, we accept also the moral responsibility of putting things right,” Kevin Over, a Pawnee Indian, said in an emotional speech marking the agency’s 175th anniversary. With tears in his eyes, Mr. Over apologized on behalf of the BIA, but not the federal government as a whole. He is the highest-ranking U.S. official ever to make such a statement regarding the treatment of American Indians. “This agency participated in the ethnic cleansing that befell the Western tribes,” he said. “This agency set out to destroy all things Indian. The legacy of these misdeeds haunts us.” The President did not apologize, and in terms of cold hard cash resulting from lawsuits this is also significant. |

| 2002 – March – “They are waiting for us to die.” | Government officials say they are moving faster to compensate those abused in Indian residential schools, but critics warn victims caught in a sluggish process are dying off. Gabe Mentuck, 73, said his claim has dragged on for six years and he charged the government is “just waiting for us to die.” He is claiming compensation for abuse that occurred at the Pine Creek Residential School in northern Manitoba in the 1940s. |

| May 30, 2005 | RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT

The Settlement Agreement is the product of negotiations launched on May 30, 2005, by the Government of Canada and the Assembly of First Nations (AFN). The Hon. Frank Iacobucci was appointed as the federal negotiator to work with all stakeholders (the AFN and other Aboriginal organizations, the Anglican, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic, and United Church entities, and legal counsel for former students) to develop a fair, final, and comprehensive resolution package to the tragic legacy of Indian Residential Schools. The General Council Executive of the United Church approved the Settlement Agreement on April 30, 2006, and the federal Cabinet did so on May 10, 2006. “This is the largest and most comprehensive settlement package in Canadian history. Today marks the first step towards closure on a terrible, tragic legacy for the thousands of First Nations individuals who suffered physical, sexual, or psychological abuse… While no amount of money will ever heal the emotional scars, this settlement package will contribute to the journey on the path to healing—not only for all residential school survivors, but for their children and grandchildren.” National Chief Phil Fontaine, November 23, 2005 |

| 2006 | Note: the recent apology by Prime Minister Harper to the Chinese Canadians (June 22, 2006) as a result of the racist head-tax imposed on them was timed when there are so very few survivors left. The head-tax was levied against almost 9,000 Chinese, now there are less than 20 still alive. One cannot help but conclude that much the same cynicism is being levied against Native residential school survivors. |

| 2007 | INDIAN RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT (INRSSA)